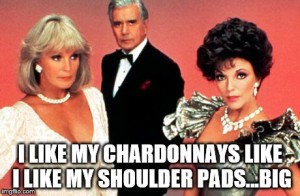

During the 80’s the US fell in love with oaky, buttery Chardonnay. We loved it the same way we loved the family intrigues and endless catfights on mainstream soap operas like Dynasty and Falcon Crest. It was a decade of big shoulder pads, big hair, and even bigger wines. How exactly do winemakers craft the big buttery Chardonnays? It’s called malolactic fermentation.

During the 80’s the US fell in love with oaky, buttery Chardonnay. We loved it the same way we loved the family intrigues and endless catfights on mainstream soap operas like Dynasty and Falcon Crest. It was a decade of big shoulder pads, big hair, and even bigger wines. How exactly do winemakers craft the big buttery Chardonnays? It’s called malolactic fermentation.

The buttery flavor found in specific Chardonnays (California Chardonnays in particular) is due to the presence of diacetyl, a naturally occurring organic compound found in wines that have gone through malolactic fermentation, and it’s the very same compound added to artificially flavored movie theater popcorn and margarine. Yup. Chew on that for a minute. Of course, this begs the question, what is malolactic fermentation?

Often referred to by winemakers as secondary fermentation, malolactic fermentation (MLF) follows on the heels of primary fermentation and, for the most part, will start spontaneously in oak-aged red and white wines. Unlike primary fermentation, which is the conversion of the natural sugar in grapes to alcohol and CO2 by yeast, MLF is a bacterial fermentation. Specifically it’s lactic acid bacteria (LAB), and like in primary fermentation, CO2 is liberated in the process. The main action of malolactic fermentation, why we do it, is the conversion of malic acid to lactic acid.

Perhaps the easiest way to understand the effects of MLF is by visualizing malic acid as the acidity found in a tart green Granny Smith apple. Then think of lactic acid, the acid found in dairy products like cultured buttermilk or butter. In red wines, butteriness is not quite so apparent, or if it is, it’s perceived as butterscotch; though it’s important to note that many commercial strains of malolactic bacteria exhibit no buttery aromas and flavors at all. MLF is prized for the softening effect it has on wines; MLF has the ability to reduce harsh acidity and astringency in young red wines in exchange for richness and body and has the ability to deliver the perception of silkiness and even creaminess. Winemakers will also argue that secondary fermentation also helps to better integrate oak into wine’s overall character.

like cultured buttermilk or butter. In red wines, butteriness is not quite so apparent, or if it is, it’s perceived as butterscotch; though it’s important to note that many commercial strains of malolactic bacteria exhibit no buttery aromas and flavors at all. MLF is prized for the softening effect it has on wines; MLF has the ability to reduce harsh acidity and astringency in young red wines in exchange for richness and body and has the ability to deliver the perception of silkiness and even creaminess. Winemakers will also argue that secondary fermentation also helps to better integrate oak into wine’s overall character.

It’s safe to assume that the vast majority of red wines undergo a secondary fermentation, an exception to this rule is Beaujolais Nouveau – and that’s an entirely separate post. It’s also safe to assume that wines that haven’t gone through MLF have retained their malic acid—think of crisp whites fermented in stainless steel.

If you want to explore the difference first hand, try a tart crisp New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc and a white Bordeaux. The Bordeaux Blanc is typically barrel aged while the New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc is not. Then pick up a Napa Valley Chardonnay. Mind – blown. If you have the opportunity, I highly suggest wine festivals like The Chardonnay Symposium or Paso Wine Fest. It will give you the chance to try various wines side by side and speak to winemakers and tasting room staff and hear their take on MLF.

As for Chardonnay, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction in favor of non-buttery Chardonnays. But still, California Chardonnay is crafted in a range of styles. Some of those early, classically-styled butter bombs still exist and are still quite popular, all in thanks to malolactic fermentation!