Why We Oak: The Whys of Wine and Wood for Wine (How’s THAT for alliteration?)

When you picture in your mind a working winery, you likely envision stacks of barrels containing that magical potential of the next vintage of wine. But why barrels? Where do they come from? What do they do for the wine?

A Brief History

Over two millennia ago, when the Romans began to spread their empire across the globe, they not only wanted to take with them weapons and food, but also wine. Wine was safer to drink than water, it provided calories to malnourished troops, and of course it provided its imbiber with an intoxicating buzz. For a few thousand years, starting with the ancient Egyptians, clay amphorae were the way armies (and traders) transported wine over long distances. There were other civilizations, primarily in the Mesopotamian region, who used palm wood barrels, but this was the exception, not the rule. While palm wood barrels weighed far less than clay amphorae, palm wood was quite difficult to bend.

The practice of using amphorae continued in Greece and then the Roman Empire. As the Romans pushed north into Europe, and away from the Mediterranean, transporting the clay amphorae grew increasingly difficult. Those buggers were heavy, and more breakable than desired. While the Romans were aware of palm wood barrels, the price and difficulty of bending the wood made them a poor choice. When the Romans encountered the Gauls, they found a group of people who were using wooden barrels, often made of oak, to transport beer. The Gauls LOVED beer…. but that’s a story for another time.

The Romans quickly realized they had found a solution to their wine transportation quandry. While other woods were used, oak was popular for a number of reasons. First, the wood was much softer and easier to bend into the traditional barrel shape than palm wood, thus the oak only needed minimal toasting and a barrel could be created much faster. Second, oak was abundant in the forests of continental Europe. And finally, oak, with its tight grain, offered a waterproof storage medium. The transition to wooden barrels was swift. In less than two centuries, tens of millions of amphorae were discarded.

After the switch to barrels, the Romans and those that followed began to realize that the oak barrels imparted new, pleasant qualities to the wine. The contact with the wood made the wine softer and smoother, and with some wines, it also made it better tasting. Due to the toasting of the wood, wines developed additional scents such as cloves, cinnamon, allspice or vanilla, and when consumed they had additional flavors present, such as caramel, vanilla or even butter. As the practice of using oak barrels continued, merchants, wine producers, and armies alike, found that the longer the wine remained inside the barrels, the more qualities from the oak would be imparted into the wine, and thus began the practice of aging wine in oak.

Benefits of Oak

Oak is often described as a winemaker’s spice rack, its flavor-imparting properties meant to complement to the wine. Some wines can handle more of it and some are produced entirely without. When done right, barrel aging can add beautiful layers to the wine further bringing out the flavors of the fruit. When in balance, it can create great depth and complexity, contributing to a wine’s longevity. As with all spice, however, a deft hand must be used so as to strike the proper balance and not over-season.

Barrel aging wine has benefits way beyond just imparting flavor.

Barrel aging wine has benefits way beyond just imparting flavor.

-A newly pressed red wine has been sitting with skins and seeds. Think about chewing on a grape skin from a berry you just picked off the vine. The skin is dry, a velvety texture. Now imagine the wine soaking all those tannins up. It can be quite harsh at a young stage in its life. For several months, the wine will sit in barrel and actually precipitate out these solids that it has acquired from the skins and seeds, softening the wine, smoothing the tannins, making it less “chewy.”-Wine barrels are also semi-porous. They will absorb some part of the wine if new but will also allow a small amount of oxygen to reach the wine, giving it an ever-so-slight aeration. It’s similar to decanting a finished and bottled wine, but very slow motion, called oxidation. During this process, the wine develops secondary flavors and aromas. (Primary aromas are mostly from the fruit itself, tertiary aromas mostly evolve in the bottle). In barrel, they can develop flavors like tobacco, tea, and vanilla, non fruit components.Malolactic Fermentation, or a secondary fermentation after the alcoholic fermentation, is often done in barrel. This process, with the help of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB or Oenococcus oeni or Lactobacillus or Pediococcus) converts the crisp malic acid (think about salivating after taking a bite of a Granny Smith apple) into lactic acid (creamy textured acid found in milk, yogurt). The wine then has a chance to develop more flavors while these interactions and processes happening at once.

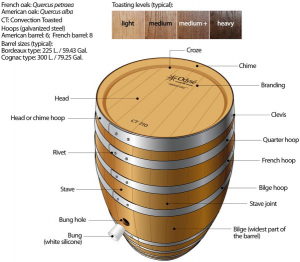

The Main Types of Oak Barrels used in Winemaking

The most popular oak used by winemakers is French oak followed by American oak and sometimes Hungarian oak. French oak, because of its finer grains, will typically impart more delicate flavors and aromas, not to overwhelm lighter wines. American oak has a much stronger influence with powerful flavors and aromas to impart to the wine because it has larger a grain. Hungarian is the third most widely used type of oak barrels and has gained popularity recently. Its worth a note that Slovenian oak has also begun to make a world wide presence in winemaking. Cost varies with the quality and provenance of the barrel, but can run as much as $900-$1500 per barrel.

So, you just got a bit of History, a bit of Craftsmanship, and about as much Chemistry as I can be expected to remember. You’ve officially earned that next glass of wine!